Medicinal Trees used for Bark

Medicinal trees are an important tool for foragers and herbalists. Many different parts of trees can be used, from their flowers and fruit all the way down to their roots.

In the wintertime, when conditions like coughs and colds have greater prevalence, we can turn to the inner bark of trees as a source of important plant chemicals to combat these ailments.

In fact, humans have been doing this for generations, and you can too! When we talk about using the “bark” in almost every case, we mean the inner bark, also known as the active phloem. This is where the chemicals that are responsible for the traditional uses of the trees can be found.

In this article, you’ll find information on several different medicinal trees with useable bark as well as my thoughts on responsible harvest and use!

Sustainability

The practice of harvesting bark for medicinal compounds is frowned upon by many, but it isn’t difficult to forage bark responsibly. I will give you a set of practices to ensure you are minimizing any damage while you build a closer connection with these trees.

How to harvest inner bark

If you are going to gather the inner bark, you want to take long vertical strips, not horizontal. By harvesting the inner bark, we’re taking away veins in the tree that run vertically. If you were to harvest all the way around, you would girdle the tree and effectively kill it.

Use the branches and twigs

I have done testing using the twigs and branch bark and found it to be a comparable substitute to the inner bark from the main trunk! This is a great way to use a non-essential component of the tree.

Use trees that must be removed

There are many cases where a tree needs to be taken down. This gives you the opportunity to make better use of the tree! Remember, in a lot of these scenarios, removing trees can be beneficial to the ecosystem. Gathering the bark for herbal uses makes that even more of a win-win.

What is a "medicinal" tree?

The term “medicinal” can get overused, so I would like to define what I mean by a “Medicinal Tree.” Simply, it is a tree that I was able to find traditional uses for from multiple trustworthy historical sources.

The main sources that I used in researching this article beyond my own experience are:

- King’s American Dispensatory 1898 by Felter and Lloyd

- Native American Ethnobotany DB

- A Reference Guide to Medicinal Plants by Crellin and Philpott

Medical Disclaimer

It’s important to state that I make no claims that any of these trees will treat or cure anything. Again, the information is based on documented historical uses and is intended to inform and educate.

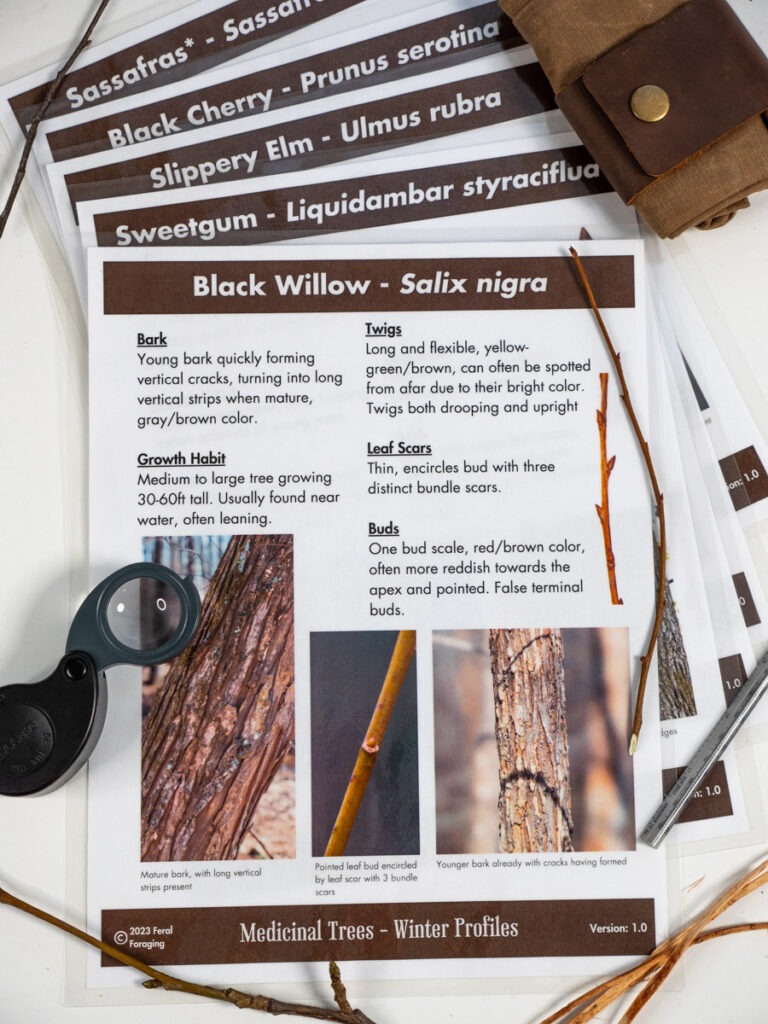

Your Winter Profile Sheets!

All of the trees in this article can be found in my set of Medicinal Trees – Winter Profiles. They contain more photos and in-depth information in a format that can be taken with you on your phone or printed out for easy access!

You can get yours for FREE using a 7-day trial on my Patreon. You can also see a preview of the set with Black Willow. Click here for the free preview.

Learning Winter Tree ID

For the identification portions of each of the medicinal trees, if there is any terminology that you aren’t familiar with, don’t worry! I have a full guide that will teach you everything you need to know. It’s called, The Ultimate Guide to Winter Tree ID.

Sweetgum - Liquidambar styraciflua

Sweetgum is an iconic tree known for the spiky seed balls it produces in massive quantities! It was a popular herbal remedy for coughs, colds, and digestive issues like dysentery. It is important to know what parts of Sweetgum to use, which is discussed further below.

It is a weedy and aggressive grower that has thrived in the era of fire suppression. You cannot harvest too much of it.

Personal Observations

Sweetgum inner-bark does not easily come off in strips. I have found it to be the fastest way to remove all the bark material from branches. I need to try to harvest the inner bark from a larger tree in the future to see if that is a viable option.

Parts Used

According to renowned herbalist Tommie Bass, the best part of sweetgum to use for its herbal applications is the inner bark in the winter and the leaves in the summer.

This conflicts with advice you’ll hear from modern herbalists to use the infertile seeds in the gumballs to extract shikimic acid to make “DIY Tamiflu.” The reason for the conflict is because the tamiflu claim is completely a myth based on an incomplete understanding of chemistry. The claim is the equivalent of saying that a block of steel can be used almost like a knife because it’s the starting material. It doesn’t make much sense to me!

You can read more about this in a deep-dive article my wife and I wrote on the subject.

Identification

Sweetgum is easily recognizable. It has mature bark with interlocking ridges. The buds have many bud scales and are exceedingly shiny. The twigs often form corky wings, and the gum-balls are usually found below the tree or clinging to the branches!

Black Cherry - Prunus serotina

Black Cherry is a tall, fast-growing, and widespread tree in Eastern North America. They produce tiny cherry fruits that vary greatly in their flavor. This tree has a long tradition of herbal applications where it is found.

It is most well-known as a cough suppressant and is generally used for colds and other respiratory conditions.

Personal Observations

It is a little difficult to achieve, but if prepared properly, you can make a bark infusion that retains the delicious aromatic cherry flavor that the bark produces. The trick is not to use too much heat.

That being said, some heat is required to evaporate off some of the cyanide that is produced from the cyanogenic glycosides in the tree breaking down. This is discussed further in the cautions section.

Identification

One of the more easily recognizable features of Black Cherry is its horizontal lenticels that are present all the way through the life of the tree. As the tree ages the bark splits and develops a “scaly” looking appearance, but the lenticels will still be visible.

Black cherry has alternating shiny brown-red buds with a true terminal bud. The twigs are also reddish brown, sometimes with a lighter gray coating on the exterior. If you scratch the twigs, they will release a pungent “bitter-almond” aroma that further clues you to its identity.

Cautions

Black cherry produces some amount of hydrogen cyanide from the cyanogenic glycosides in the bark. The amounts produced are likely not that large, but in order to remove cyanide content, you just need to heat your infusion liquid to at least 78 degrees Fahrenheit, which is the boiling point of liquid cyanide. It will then evaporate off.

I’ve seen claims that cyanide is the responsible component for suppressing the cough, but I haven’t found compelling information to believe this is true.

Get my foraging guide!

Learn an amazing wild food for each month of the year with my guide, Foraging through the Seasons!

Enter your email below to have this FREE guide sent straight to your inbox!

Black Willow - Salix nigra

Black Willow is commonly found along streams, rivers, and wet lowland areas. It is one of the more common willow trees native to Eastern North America.

Traditionally, it has been used to reduce fevers and alleviate stomach issues.

Personal Observations

Black willow bark is easy to harvest in long vertical slices. I also make tea with the twigs and bark of the branches. An infusion of black willow bark is extremely bitter, so be prepared!

Historical Use and Chemistry

Historically, Black Willow has been used more for its fever-reducing and digestive benefits rather than for pain relief specifically. Willow trees (Salix) are known to contain salicin, a chemical that converts to salicylic acid in the body. This chemical is similar to the active ingredient in Aspirin, acetylsalicylic acid.

A well-designed study found that extracts of willow bark standardized to salicin were effective at treating lower back pain. The caveat is that salicin content in willow species varies dramatically. Unfortunately, black willow has not been analyzed yet.

Winter Identification

Black willow is very easy to find once you are in the right location. Look for the vibrant orange-yellow, long flexible twigs that curve upright and trees that often lean with bark that has long vertical strips.

Usage Cautions

If you are allergic to Aspirin, you are likely allergic to willow as well. Additionally, children should not use willow, nor should people on blood thinners or those who are pregnant.

Sassafras - Sassafras albidum

Sassafras is an iconic aromatic tree and is now extremely controversial regarding its use. This was once the principal flavoring component of root beer. However, the main chemical responsible for the distinct flavor, safrole, is now an FDA-banned substance because of its carcinogenic properties.

I am completing a deep-dive on this subject as of writing this article on the legitimacy of the carcinogen concern with safrole. For now, I must advise you to consume at your own risk.

Personal Use

I always want to personally test out the wild food and herbs that I teach all of you about. Despite the carcinogen concern, I felt comfortable enough consuming a small amount of the bark tea after boiling for about 15 minutes (boiling may reduce the safrole content). The tea produced has a deep, beautiful red color and, indeed, is incredibly delicious.

Again, though, I’m afraid that at this time, I am not comfortable recommending its use to others.

Traditional Uses

When we investigate the historical uses of Sassafras, we will find a myriad of purported applications. I will describe the ones that I consistently found across multiple sources.

Sassafras was used both internally for conditions like parasites, fevers and chills, and venereal diseases (this may have been external as well). Externally, it was used as an antiseptic for cuts and sores and as an eye wash.

Sassafras bark has some mucilaginous compounds as well, which may be why it was additionally regarded as a demulcent or soothing herb.

Identification

Sassafras has bark with large intersecting ridges, often with horizontal breaks. If you scratch away a layer of the outer bark, it will reveal a very red color on the inside.

The tree has large, prominent terminal buds with overlapping bud scales but much smaller lateral buds. The twigs are usually green and very smooth. If cut a twig, it emits a strong but pleasant and somewhat sweet aroma.

Slippery Elm - Ulmus rubra

Slippery elm is found in many parts of Eastern North America. It is more abundant in some areas than others due to the local impacts of Dutch Elm Disease. There are claims that slippery elm is endangered despite its “least concern” conservation status. While the official conservation status can be inaccurate, there is, unfortunately, not a great amount of formal literature on the subject. It is difficult for me to form an accurate opinion on the greater abundance of slippery elm because it is relatively common in my area.

Nonetheless, I have a solution for all of us that is discussed further in the sustainability section.

Traditional Use

Slippery elm gets its name from the mucilaginous liquid that is produced by mixing its inner bark in water. I’ve heard a lot of people say they don’t like the flavor very much, but it is always from bark they ordered online. I have found slippery elm tea made from my own wild-harvested bark to be sweet and delicious.

I usually use some heat to make my slippery elm tea, which is indeed incredibly soothing.

Traditionally, it was used for conditions like sore throat and digestive complaints, and generally to help people recover from ailments.

Winter Identification

Slippery elm has a mature bark with long intersecting ridges that have flat tops. The buds are very distinctive. They are somewhat blunt with dark brown, almost black bud scales usually accompanied by orange-brown fuzzy hair towards the top.

Sometimes, I find it easier to spot Slippery elm by the numerous dark round buds on its branchlets high in the tree. The twigs are rough and hairy as well. If you take a cross-section of the outer bark, it will be relatively uniform in color, a dark orange-brown, compared to American elm, which has distinct coloration zones, almost like an Oreo.

Sustainability Concern

As I stated earlier, in my opinion, we don’t have enough information to clearly conclude the conservation status of slippery elm at this time. You can refer to the section at the beginning of this article for general sustainable harvest practices like using branches (what I always do). Still, with slippery elm, there is an even better solution: harvest its invasive cousin, Siberian elm (Ulmus pumilla).

If you have slippery elm in your area, there is a good chance you have siberian elm as well. This is an aggressively growing invasive tree from Asia. It also contains mucilaginous compounds, and in my own testing, I’ve found it to be nearly indistinguishable from slippery elm.

I would love to see this invasive tree replace slippery elm in the realm of commercial harvest, as I do not condone the commercial harvest of slippery elm! I would much rather see people form their own individual relationships with this incredible tree.

Closing Thoughts

A lot of people make it seem like using bark for medicine can only be a bad thing, deterring herbalists and foragers from even attempting to try. I think they’re wrong.

Especially in the wintertime, when there aren’t many other things to forage, gathering bark, branches, and twigs offers an opportunity that continues to bring out outside, into nature, to develop a closer relationship with these important species.

I hope this article helps to offer a different perspective and empowers you with the information you need to take the first step!