Introduction

This is a guide to foraging in Alabama. It covers an array of wild species common in the state and the Southeast. I felt like there were not many good resources for foragers in the Southeast, so I decided I wanted to remedy the situation!

My name is Jesse. I am a forager from North Alabama. I have been meticulously scouting, documenting, and, of course, eating wild species throughout the state for nearly a decade! I have personally worked with and consumed every species included in this article.

If you are a new forager, welcome! I highly recommend reading our How to Start Foraging article before you begin. It provides a map laying out everything you need to know to start your foraging journey, including important topics like safety and responsibility.

Once you’ve done that, you can jump into the profiles in this guide!

How to use this guide

This guide is divided into several sections based on the type of wild food product. The sections include shoots, greens, flowers, fruit, nuts, and fungi. The species within each section are ordered alphabetically by their common names, but the scientific name is also listed. In some cases where multiple species are represented in a section, you’ll only see the genus (e.g., Brambleberries – Rubus).

Each section also contains a write-up of my experiences with that specimen and a short section on identification. I would encourage you to look up additional resources for this article if you are foraging something for the first time. The profiles are not intended to be used as comprehensive instructions but to point you in the right direction.

The foraging guide also applies almost entirely to neighboring states in the Southeast like:

- Tennesse

- Georgia

- Mississippi

- Kentucky

- North Carolina

- South Carolina

- Texas

- Arkansas

Learning more

If you are interested in Southeast foraging, you would be a perfect fit for our Foraging Discord community! We’re a group of hundreds of foragers like you that you can learn alongside. It’s a great place to get additional guidance and help with topics like processing and identification.

A lot of these species have been covered by me as a video on my YouTube channel. I’ve included links to additional video resources and other articles on my website.

I put a lot of work into this guide and hope you find it helpful! As you read, if you are finding it providing value, I would love it if you shared it so it can help even more people!

Support my work

If you would like to support my work of providing foraging education for all and get exclusive access to foraging classes and monthly Q&As consider trying out a free 7-day trial of my Patreon page. It allows me to continue providing education content like my videos and articles for free and gives you access to in-depth classes!

Wild Greens and Shoots in Alabama

When people think of wild edible plants in Alabama, one of the first things that comes to mind is wild greens. You will find a few typical edible plants missing from this article, replaced with comparable species that are better or more common in Alabama.

For instance, instead of including dandelion, I will tell you about Canadian wild lettuce, which is far superior in taste and texture in the Southeast. Additionally, a popular wild green, stinging nettle isn’t common in the Southeast, so I’ve replaced it with its more common and just as delicious cousin, wood nettle.

Wild greens can have a short window as our Spring often rockets straight into warmer Summer temperatures. We have a slightly larger window for Spring shoots. Shoots are often overlooked as a vegetable from foraging, but they shouldn’t be! Alabama has an array of tender shoots to eat, like sumac and thistle. They are all discussed in the article!

Canadian Wild Lettuce - Lactuca canadensis

Everyone rants and raves about dandelion greens which, are my area of the Southeast, typically grow tough and bitter quickly. I pass on dandelion greens and instead seek out young wild lettuce rosettes. Not all wild lettuce species are created equal for culinary applications. The ones you want are one of L. biennis, L. canadensis, or L. foridana. (My favorite being L. canadensis)

Other common species like L. virosa or L. serriola will be acrid and bitter even when young!

Wild lettuce greens are everything that dandelion is not. They have a crispy juicy texture. They are only slightly bitter (sometimes even after bolting) and they can be gathered well into Spring.

If you want to learn how to identify wild lettuce, I have an article on my website. If you instead are interested in herbal applications rather than culinary ones, I have a video and article on that as well!

Identification:

- Hairs growing along the midrib

- Compound flower heads yellow to purple

- First-year growing as a rosette, second year sending up a stalk

- Leaves on stalk alternate and obovate to runcinate

- White latex sap exudes where cut or broken

- Can grow quite tall sometimes up to 10ft

Chickweed - Stellaria media

Chickweed, Stellaria media, is one of North America’s most well-known wild greens. It is a low-growing Spring green with a crisp texture and good flavor.

Chopped greens make a great addition to any salad.

Identification:

- Opposite, simple leaves

- Line of hairs between leaf nodes that alternates side up the stem

- White flowers with five divided petals creating the appearance of 10 petals

Pokeweed - Phytolacca americana

Pokeweed is one of the Southeast’s most iconic and controversial wild foods. You may have heard it described as “deadly toxic,” but this is a drastic over-exaggeration of its toxicity.

While poke does have toxic components in its raw parts, it has been consumed with proper preparation for generations, and foragers like me still eat it today.

Here is how I prepare it – I gather the young, tender greens and shoots in the Springtime. Once gathered, I peel the shoots and remove the greens to cook separately. I boil the poke for seven minutes, then strain out the water. I add water back to the pot, bring it to a boil again, and boil it for two more minutes before straining once more.

Then I taste my greens and shoots. If they are excessively bitter or acrid, I do an additional boiling change of water. If not, I sauté with a fat like bacon grease or butter before serving. I have consumed poke for years this way without issue.

Many people also talk about consuming the berries. I don’t eat the berries. All I can say is they taste terrible, and I have no reason to consume them. I think people are interested in their medicinal application, but I’m not an herbalist, so I cannot comment on this practice or its efficacy.

Identification:

- Reddish-purple stems, up to 10 feet tall, typically hollow

- Leaves large, simple, alternate, lanceolate to oval, up to 20 inches long

- Small, white flowers in elongated clusters (racemes), blooming from May to October

- Berry-like fruit, green turning deep purple or black when ripe, containing several shiny, black seeds

- Large, fleshy taproot

Purple Deadnettle - Lamium purpureum

Believe it or not, this plant, regarded as a common weed, is one of my favorite wild herbs. Many people talk about sautéing these or eating them as a salad green. I think they taste awful in both of those contexts! My way to consume them is as tea!

I gather the aerial parts of the wild herb, then dehydrate them on low. From here, I’ll rub them together or blend them to increase the surface area and steel in boiling water for about 10 minutes. The tea reminds me of nettle tea (funny, despite this one being “dead” nettle), and I really like it!

Identification:

- Square stems, typical of plants in the mint family, growing 5-30 cm tall

- Leaves are triangular to heart-shaped, with a toothed margin, and are often purple-tinged at the top of the plant

- The lower leaves are larger and greener, while the upper leaves become progressively smaller and more reddish-purple

- Produces small, pink to purple flowers, with a hood-like upper petal and a three-lobed lower petal

- Flowers appear in whorls in the leaf axils, blooming from early spring to late fall

- Grows as a ground cover, often in disturbed areas like gardens, fields, and roadsides

Sochan - Rudbeckia laciniata

Sochan is a lesser-known but incredibly delicious wild green that was introduced to me by Samuel Thayer. It is an Aster family member and produces beautiful yellow flower heads in the Summer!

The young tender leaves and shoots are the part that is consumed. Reportedly, there may be some concern that raw greens of sochan are slightly toxic, so light cooking by steaming or blanching is advised, and it also improves the flavor!

Caution:

A potential lookalike to sochan are some members of the Buttercup family that are bitter and acrid tasting (and mildly toxic). The leaves can be confusing when young, so if foraging sochan for the first time, the easiest way to identify them is in the summer when the flowers have developed as they are not similar to buttercup flowers.

Identification:

- Yellow compound flower heads (both ray and disk flowers)

- Deeply divided leaves almost looking pinnately compound

Sumac Shoots - Rhus spp.

Another underrated wild vegetable, sumac shoots! Like other shoots we forage for, these are best harvested when young and tender. They should bend easily.

If you find sumac at this stage, peel the outer skin and get to munching! The flavor is great, and the texture is both juicy and crunchy. Not one to miss!

There are several species this can be done with. In my area, smooth sumac, Rhus glabra is best! Staghorn sumac Rhus typhina may also be good, but they don’t grow in my area, so I have not confirmed yet.

When you hear “sumac,” many immediately think of “poison sumac,” which isn’t a sumac at all. Poison sumac’s stems tend to be far more red in hue than true sumac and have leaflets that are not serrate.

Identification:

- Stems light green

- Leaves serrate (except for winged sumac) and pinnately compound

- Leaflets can have a red/purple color in the early springtime

- Broken stems and leaves yield white latex

Thistles - Carduus, Cirsium

The term “thistle” refers to a group of plants in the Aster family that have sharp bristly leaves and stems. In my area, common species include Musk Thistle Carduus nutans, Tall Thistle Cirsium altissimum, and Bristle Thistle, Cirsium horridulum.

My favorite food product from thistles is their shoots.

Admittedly, this preparation takes some care to avoid the spikes, but you are rewarded with a refreshing juicy wild vegetable at the end! Like other wild shoots, harvest when tender.

Identification:

- Sharp-pointed leaves and stems

- Typically purple to red compound flowerheads (they look “fuzzy”)

- Biennial, growing as a rosette the first year and sending up a shoot he second

Watercress - Nasturtium officinale

Watercress is an iconic wild food that both foragers and chefs revere! This crisp and peppery green is a member of the mustard family and likes clean, cold water streams.

The best place to find watercress is cold spring-fed streams.

Caution:

With water species like this, there is a concern about contracting parasites like the liver fluke. This is the case in water that is downstream of cattle fields. Liver fluke cysts attach to below-water portions of watercress. To forage watercress safely:

– Never gather downstream of cattle fields

– Gather above water parts (including fluctuation of water levels)

– Blanch plant parts before consuming

Identification:

- White, four-petaled flowers

- Growing in water

- Leaves pinnately compound, 3-7 leaflets

Wild Carrot - Daucus carota

Wild carrot, or “Queen Anne’s Lace” (QAL), is one of the most notorious wild foods due to its resemblance to a potentially deadly plant, Poison hemlock Conium maculatum, so let’s talk about that first.

To an unseasoned forager or naturalist, they can indeed look similar; however, with a few distinguishing details, we can easily tell them apart.

QAL has hairy stems and leaves; poison hemlock has smooth stems and hairless leaves. QAL does not have purple splotches on the stem; poison hemlock does. QAL typically grows to about 3 feet high and bears a single flowering head; poison hemlock grows past 6ft tall and bears multiple flower heads per stem. QAL often has a purple flower in the center; poison hemlock does not. QAL has a prominent bract at the base of its compound umbel, often called the “skirt”; poison hemlock does not.

We can go on, and I encourage you to observe the differences between these two in the field.

A common piece of misinformed and dangerous advice is to just use the aroma of the roots to distinguish because “wild carrot smells like carrot.” While this is true, in my experience, poison hemlock roots can smell like carrots, too. NEVER use a single detail to distinguish an edible plant from a deadly one, especially a detail that is variable, like aroma.

This brings another component of safe foraging into the picture. We know that 100% identification confidence is a pre-requisite for consumption, but another that my friend Orion Aon introduced to my teaching is being 100% comfortable. It took several seasons of observing wild carrots and poison hemlock before I became comfortable consuming wild carrots despite being 100% confident of my identification within the first year. You don’t get bonus points for knocking things off your “to forage” list faster, so take your time!

With all that out of the way, the most common part of the plant that I consume is actually the peeled shoots. Like other spring shoots, they should be tender if eaten!

Identification:

- Leaves deeply divided to tripinnate

- Leaves and stems hairy

- Single stem yield single compound umbel flowerhead

- Flowers white, often with a deep purple flower in the center

- Growing to around 3ft in height

- Prominent bract underneath the flowerhead often called a “skirt”

Wood Nettle - Laportea canadensis

Everyone rants and raves about the European Stinging Nettle, Urtica dioica, but far fewer people know about its equally (if not more) delicious cousin, Wood Nettle. They are more common in Alabama, where I forage than stinging nettle.

While they both sting if the needles brush your skin and the shape of the leaves is similar, wood nettle can be easily distinguished from stinging nettle by its alternate arrangement of leaves.

I like to steam my wood nettle to eat them. They have a slight “fish” umami flavor that I quite enjoy!

Identification:

- Greenish stems covered with stinging hairs, reaching up to 1 meter in height

- Alternate, ovate to lanceolate leaves, 6–15 cm long, with serrated edges and stinging hairs

- Small, greenish flowers, unisexual, with separate male and female flowers on the same plant, blooming from late spring to early fall

- Fruit is a small, greenish achene

- Top leaves larger than bottom leaves on mature plants

Wild Edible Flowers in Alabama

There are more edible wildflowers than I could count, so I’ve only included ones you can gather a substantial amount of without too much trouble.

When foraging for flowers, remember that this means you won’t be getting fruit down the road. There is a balance to play here with plants like elderberry, but it can be an advantage with invasive plants like multiflora rose!

Black Locust - Robinia pseudoacacia

I cannot think of an aroma more delicious and intoxicating than the blooms of black locust. This native pioneer tree produced beautiful white blooms that are edible!

They can be used in both a sweet and savory context. My favorite use is as syrups and jellies. I gave a bunch to a friend once who made an amazing mead with them as well. I often eat them raw off the tree before they have even hit my basket. They can also be sautéed in various dishes, yielding cooked flowers with a sweat bean flavor.

I am told that honey made from bees foraging black locust nectar is some of the best tasting in the world!

I recommend you plant this native species on your land, but be aware that as a pioneer tree, it can get out of control as a pioneer tree if not managed.

Note: Only this tree’s flowers and properly prepared beans are edible. All other parts are toxic.

Identification:

- Bark is dark brown and deeply furrowed

- Branches may have short, sharp spines, especially on younger trees

- Alternating compound leaves with 7-19 oval, smooth-edged leaflets, each 1-2 inches long

- White, fragrant, pea-like flowers in hanging clusters, blooming in late spring

- Seed pods green turning dark brown, 2-4 inches long, containing 4-8 seeds

- Mature trees can reach 40-100 feet in height

Elderflower - Sambucus

A lot of people know about elderberry due to its herbal uses as a cold remedy, however, my favorite part of the elder tree is actually its flowers!

Elderflowers come in large white clusters called “compound cyme.” Individual flowers are five-petaled with yellow stamens. Whether you are interested in the fruit or after the flowers, the best time to find elder is when it is flowering. You may be surprised at how much you see growing on roadsides!

If foraging the flowers, it is important to be able to distinguish elder from water hemlock as unaware beginners have been known to mistake them! There are many characteristics that separate them. Elder develops woody bark with lenticels. Water hemlock is herbaceous without lenticels. Elder has a spongy pith in its stems and branchlets. Water hemlock stems are hollow. Elder has once-compounded pinnate leaves that are opposite. Water hemlock has tripinnate compound leaves that attach to the stem with a “sheath” like material and are alternate. With a few details, it is easy to tell them apart, you just need to know what to look for! I encourage you to study this more. If you are interested, I have a video on distinguishing them on my channel!

Identification:

- Shrub or small tree, typically growing 5-12 feet tall with stems rarely exceeding 3 inches in diameter

- Compound leaves with 5-11 leaflets (usually on the lower end), each leaflet lance-shaped to oblong, 2-5 inches long, with serrated edges

- Bark is light gray to brown, with shallow furrows and raised lenticels

- Large clusters of small, white to cream flowers, forming flat-topped or slightly rounded cymes, blooming in late spring to early summer

- Prefers wet or moist locations such as stream banks, lakesides, and damp clearings

Multiflora rose - Rosa multiflora

A stunningly beautiful yet horribly noxious invasive plant. Multiflora rose is common along forest and field edges, producing beautiful clusters of white wild rose flowers. It puts on tiny red rose hips in late autumn and winter.

Both the hips and flower petals are edible. You are highly encouraged to forage (and promptly remove) this invasive plant.

My favorite way to use this plant is to make wild rose jam. I gather as many petals as possible and process them with sugar and pectin in boiling water. The aroma and flavor this jam produces is incredible. Rose isn’t common in North American cooking, but I encourage you to try it!

Invasive multiflora rose can be distinguished from native by their rough, nearly spiky stipules vs. native roses’ nearly smooth stipules. Stipules are leafy growth at the base of petioles. In addition, native roses tend to have more vibrant pink petals.

Identification:

- Somewhat spiky or hairy stipules

- Arching stems that are green to red, covered with small, curved thorns

- Compound leaves with 5-11 oval, toothed leaflets, each 1-2 inches long

- Small, fragrant white to pink flowers, about 1 inch in diameter, blooming in late spring to early summer

- Fruits are small, round, red or orange rose hips, persisting into winter

- Can form dense, impenetrable thickets

Wild Fruits in Alabama

Alabama has a diverse set of wild edible fruits available to foragers! From ridiculously abundant persimmons to fields full of wild blueberries, there is something for everyone!

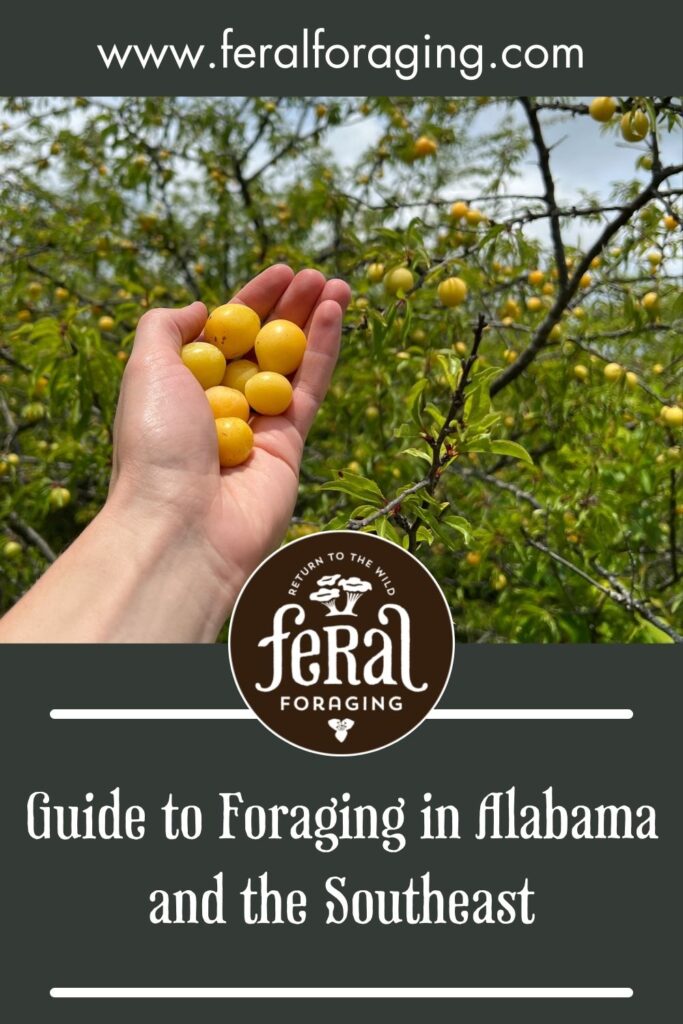

When I think of wild fruit in Alabama, the first that comes to mind is the Chickasaw plum, a wild plum species concentrated in the Southeast. That’s why I chose it as the featured image for this article!

Wild fruit is a great introductory wild food for beginner foragers as they typically have fewer lookalikes that are easier to tell apart.

I am working on a Common Wild Fruits class, which will be hosted on my Patreon! To support my work and get access to other exclusive classes like this, consider trying out a free trial.

Black Nightshade - Solanum nigrum complex

Black nightshade is another controversial wild food. The controversy is almost entirely due to an unfortunate close naming to a more well-known “Deadly” nightshade. The two plants could not be more different.

Black nightshade is Solanum nigrum complex (several closely related and similar plants), while deadly nightshade Atropa belladonna is in a different genus! I’ll show you how to tell them apart, but in my opinion, they would be difficult to mistake to begin with! Also, I have never found deadly nightshade (native to Europe) in the wild in Eastern North America.

Black nightshade has berries that come in clusters. Deadly nightshade has berries that are borne singly. Black nightshade has a small calyx relative to the fruit. Deadly nightshade has a large calyx relative to the fruit extending past its edges. Black nightshade flowers are white and star-shaped. Deadly nightshade flowers are purple and funnel-shaped! We can keep going (and I do in a video on my channel), but if you are worried about mistaking them, observe the plants when they are flowering, as they are completely different at this stage!

Two food products are consumed around the globe (even today) from black nightshades: fruits and greens. The fruit should be eaten when dark purple and ripe (it tastes very bad when green). The greens are harvested when the plant is young and tender and are usually prepared by boiling with a change of water like pokeweed. Also, like pokeweed, they shouldn’t be bitter to taste, so you can adjust the water changes if needed.

Many people don’t believe me when I tell them that black nightshades are not toxic. Sam Thayer’s book Nature’s Garden has a fantastic essay on the undue fear surrounding this plant that I encourage you to read. He cites that over 2 billion people around the globe have consumed this plant for generations and still do! I will add that the common “garden huckleberry” product in many seed catalogs is nothing more than a species of black nightshade! I guess Garden Huckleberryysounds safer as a name.

I have consumed ripe black nightshade berries every year in large amounts without issue.

Identification:

- Grows as an annual or sometimes perennial herb, typically reaching heights of 1 to 3 feet, usually wider than it is tall

- Flowers are small, white, star-shaped with five petals, arranged in clusters, blooming from mid-summer to early fall

- Fruits are small, round berries, initially green, turning purple/black when ripe

- Calyx of fruit does not extend past edges

- Commonly found in disturbed areas, such as fields, gardens, and roadsides

Brambleberries (Blackberry, Black Raspberry, Dewberry) - Rubus

Blackberries and related bramble berries are among the most common fruits in the wild. There are many different but difficult-to-distinguish species within this group in the Rose family.

I treat all blackberries the same in my area, but hold a special place for the blackcap or black raspberry. These are far more delicious to me, plus their thorns are less menacing than blackberries. Black raspberry is easily distinguished from blackberries by its hollow center compared to blackberry fruits which are solid.

In the wild, fruits come in many shapes and sizes. I generally skip the small ones and save my energy for a patch with larger, easier-to-gather fruits!

Identification:

- Stems (canes) are often arching or trailing and are covered in thorns; some species have stem hairs or are smooth, stems often channeled

- Compound leaves with 3-5 leaflets, typically oval to lance-shaped, with toothed margins; some species have leaves that turn red in the fall

- Leaves alternately arranged, with the underside often paler

- Flowers are small, white to pink, with five petals, blooming in late spring to early summer

- Fruits are aggregate of drupelets, starting red and turning black when ripe, with a characteristic sweet-tart flavor

- Habitats vary widely, from woodlands and meadows to roadside and disturbed areas

Blueberry - Vaccinium

Wild blueberries are a treat. What they lack in size compared to their grocery store relatives, they more than makeup for in flavor!

Many wild blueberry species are found in Alabama, and they aren’t all created equal. We also have relatives of blueberries like sparkleberry (Vaccinium arboreum), which is very common. I wouldn’t regard sparkleberry as choice eating compared to blueberries, but it’s still worth gathering, in my opinion!

Look for hanging bell-shaped flowers in the Spring and Summer that will eventually produce deep blue delicious wild fruits!

Identification:

- Shrubs, typically low-growing, often no more than a few feet tall

- Small, alternate, simple leaves, oval to lance-shaped, with smooth or finely toothed margins

- Leaves are often a glossy green, turning red or purple in autumn

- Flowers are small, bell-shaped, white to pink, blooming in late spring

- Fruits are small, round berries, initially green, turning blue to purple-black when ripe, often with a whitish bloom

- Berries have a sweet, tangy flavor, and are a popular edible fruit

- Found in a variety of habitats, often in acidic and sandy soils, including forests, bogs, and heathlands

Elderberry - Sambucus

Elderberry fruit has different lookalikes like pokeweed or devil’s walking stick berries. Here again, it only takes a few details to distinguish them.

Elder has opposite compound leaves, pokeweed has simple alternate leaves, and devil’s walking stick has massive tripinnate alternate leaves. Additionally, devil’s walking stick has thorns all along its stem (where it gets its name) and elderberry does not.

Once I’ve harvested my elderberries, I have found no easier way to process them than with the “freeze” method. I place them all onto a cookie sheet lined with parchment paper then let them freeze completely. From here, it’s painless (and fun) to rub the clusters together and watch all the individual fruits fall off!

I never eat elderberries raw and don’t recommend you do either. Many people have a nauseating reaction to consuming them raw, and in my opinion, they don’t taste good this way either! You may have heard that elderberry is dangerously toxic due to it containing cyanogenic glycosides, but this fear is largely overblown. The glycoside content is lower than other common foods like flaxseed or raw almonds and is largely removed from cooking.

Instead, I use them in cooked preparations like, jelly, syrup, and my favorite, wine!

Identification:

- Shrub or small tree, typically growing 5-12 feet tall with stems rarely exceeding 3 inches in diameter

- Compound leaves with 5-11 leaflets (usually on the lower end), each leaflet lance-shaped to oblong, 2-5 inches long, with serrated edges

- Bark is light gray to brown, with shallow furrows and raised lenticels

- Large clusters of small, white to cream flowers, forming flat-topped or slightly rounded cymes, blooming in late spring to early summer

- Fruits are small, dark purple to black berries in large clusters, ripening in late summer to fall

- Prefers wet or moist locations such as stream banks, lakesides, and damp clearings

Maypop, Passionfruit - Passiflora incarnata

It blows my mind how much that passionfruit costs at the grocery store. Perhaps even more crazy is that we go to such lengths to import a “tropical” fruit when another is growing in our own backyards!

Eastern passionfruit, commonly known as “Maypop,” is a vining plant that produces beautiful purple blooms. Those flowers give way to green oval-shaped fruits that ripen in Autumn. They will be yellowish and slightly crinkled on the outside with an overt fruit aroma when ripe.

On top of providing delicious fruit to us, the plant is also an essential host to the Gulf fritillary butterfly.

Identification:

- Climbing or sprawling vine with tendrils for grasping support

- Leaves are alternate, deeply three-lobed, 6-8 inches long, with a serrated margin

- Distinctive flowers, 2-3 inches in diameter, with a complex structure including a fringed corona, five white-to-purple petals, and five sepals that are purplish or blue

- Blooms from early summer to fall

- Produces oval, yellowish-green fruits, 2-3 inches long, called maypops

Mulberry - Morus

There are both native and nonnative mulberries common in North America, with many people mistaking the nonnative White mulberry Morus alba for the native Red mulberry Morus rubra.

People see a red berry and assume it must be the red mulberry. However, this isn’t the case! In fact, nonnative white mulberries produce red berries far more often than white berries (I’ve only found a true white berry-producing tree once before).

If you are finding your mulberries in a neighborhood, they are most likely the nonnative species. They have smaller, glossier leaves than the native species. Both berries are perfectly edible!

The easiest way to harvest them is to place a tarp under a tree with ripe fruits and shake the tree. The fruits that are ready to eat should fall off easily!

Identification:

- Alternate, simple leaves with serrate margins and a rough texture (rougher and larger on native species)

- Leaf shape variable from unlobed to 2-3 lobes

- Small, inconspicuous, greenish flowers; male and female flowers usually on separate trees

- Fruits are elongated, resembling blackberries, starting green and turning red to dark purple when ripe

Paw Paw - Asimina triloba

What a wild food treat that paw paw is. Due to its properties of not ripening when if picked underripe, combined with its propensity to over-ripen quickly, paw paw has never drawn much attention as a cultivated fruit. This is of no concern to foragers.

Paw paw fruits become ripe in the late summertime. Like other wild fruits, trees can be found all over, but fruiting trees require particular conditions. I have the most paw paws along open waterways where the trees get plenty of access to sunlight.

The taste is somewhere between a banana and a mango to me. This is one of those fruits that I eagerly look forward to foraging every season!

Identification:

- Large, simple, alternate leaves, 10-12 inches long and 4-5 inches wide, oblong-lanceolate in shape, with smooth margins

- Leaves are dark green in color, turning yellow or brown in autumn

- Trunks usually slender, with a grayish-brown bark

- Produces large, purple, six-petaled flowers, about 1-2 inches across, blooming in early spring

- Fruits are large, green, and oblong, typically 2-6 inches long, occurring in clusters, turning yellowish-brown when ripe

- Grows as a small tree or large shrub, often forming clonal colonies

Persimmon - Diospyros virginiana

This is my favorite wild fruit. I have yet to encounter a year where I cannot easily get an abundant harvest of American persimmon. This tree grows across Eastern North America and drops a bounty of round orange fruits.

American persimmon is notorious for its potential to be astringent. Perhaps more people than not have experienced the mouth-drying experience of consuming an unripe persimmon! However, once ripe, this fruit’s sweet and sometimes caramelized flavor is pristine!

I gather my persimmons off of the ground when they are soft and somewhat translucent in hue. They will readily dissolve into a jam, so be careful as you harvest them! From this point, they can be washed and used as a jam or for other recipes. They work very well in baking and can be used in place of bananas!

If you are interested, I have videos on my channel on how I process large amounts of persimmons.

There is an unfortunate myth that persimmons only ripen after the first frost. This is entirely untrue. I find further evidence every single year as I gather perfectly delicious and ripe persimmons months before any signs of frost.

Look for persimmon trees in parks, field edges, and open areas for the most abundant fruiting.

Identification:

- Bark is dark gray to black, deeply furrowed, forming distinct blocky or scaly plates

- Leaves are simple, alternate, oval to oblong, 2-6 inches long, with smooth margins, glossy green on top, paler underneath

- Small, bell-shaped, yellowish-green to white flowers, with male and female flowers on separate trees

- Fruits are round, 1-2 inches in diameter, initially green turning to orange or purplish when ripe

Sumac fruit - Rhus

There are so many incredible uses for the fruits of sumac! The fruit coating can be ground into a spice (I have a video on this on my channel), yielding a native sumac spice you don’t have to pay anything for!

Additionally, in the summertime, during a period without rain, the fruits will develop a sticky sour coating that can be used to make a native lemonade without any lemons. I call this “sumacade.”

Mistaking the berries of sumac for “poison sumac” (which isn’t a true sumac at all) would be nearly impossible. The fruits of poison sumac droop down and are white, while the berries of true sumac are red and point up! (I have a video on distinguishing them further if you are interested)

Identification:

- Red fruit clusters that point upwards

- Gray bark with rough dots “lenticels” present

- Broken stems and leaves yield white latex

- Shrubby growth habit

- Pinnately compound leaves usually with serrate margins

Wild Nuts in Alabama

Wild nuts are important, really important. Two of the most significant wild calorie sources fall into this group: acorns and hickory nuts. I have dedicated hundreds of hours to learning to gather and process these wild foods, mostly with acorns, but now I’m turning to hickory nuts.

I have a virtual class, The Ultimate Guide to Eating Acorns, if you want to learn everything I know about it! It’s available on my Patreon, which you can access for FREE with a 7-day trial.

As I explore more about working with hickory nuts, Patreon supporters will be the first to learn from my findings!

Acorns - Quercus

Acorns are the wild food that I have the closest relationship with. It is one of the most important food sources from the wild and comes from one of the most important trees in their ecology, oaks.

It’s hard to describe how many wins come from foraging for acorns. The only downside is that they need to be processed before consuming. Acorns contain tannins, which, in addition to being astringent and unpalatable, are not safe to be consumed in excess long-term.

Despite that, I can’t think of any wild food that is more rewarding to work with. Acorns can provide you with two major food products: flour and starch. Both can be used for a wide variety of culinary applications.

If you are interested in foraging and processing acorns for food, I have an entire series dedicated to teaching you how to do it! Check out my channel to learn more.

Identification would be difficult to include for this section, as oaks vary widely in their appearance. Know that all acorns are perfectly safe to eat with processing, so I encourage you to find the oaks in your area and learn how to identify them!

I prefer oaks that produce acorns that are large and dry well. My favorite species include Q. macrocarpa, Q. montana, and Q. rubra.

Identification:

- Small to large trees

- Simple and alternating leaves usually clustered at the ends of twigs

- Leaves often with wavy edges or pinnately lobed

- Produce acorn nuts with a distinctive cap

Black Walnut - Juglans nigra

Black walnut is one of the most iconic wild nuts of North America. Its large green-hulled fruit drops by the hundreds in autumn. Unlike some of its relatives, black walnut shells are robust and nearly unyielding to cracking, but the large nuts inside are well worth the trouble.

Everyone has a different way of gathering hulling and processing their nuts. Here is mine.

I usually smash the hulls where I find them by simply stepping on them or using a heavy stick. From here, I throw them in a container with water and remove the floaters. I use a hose to wash their exterior, but don’t worry about getting them perfect. Then, I place them in a single layer where they get plenty of airflow and leave them to cure for several weeks.

For cracking, I’m currently experimenting with different methods. As of right now, it is just a tried and true hammer along with clippers and a nut pick, but I have other nut-cracking tools on the way for me to test!

Identification:

- Dark, deeply furrowed, thick bark that forms rough, interlocking ridges

- Alternate, compound leaves, 1-2 feet long, with 11-23 leaflets usually lacking a terminal leaflet

- Leaflets are lanceolate, finely toothed, and have a slightly hairy underside

- Male and female flowers are separate but on the same tree, with male flowers in drooping catkins and female flowers in short spikes

- Fruits are large, round, green husks enclosing a hard, brown-black nut with a deeply grooved surface

- Typically grows 70-100 feet tall, with a large, spreading canopy

Hickory nuts - Carya

Hickory is another of the more significant calorie and nutrition sources from the wild. There is an array of hickory species, and all of them are edible, though a few exceptions, like Bitternut hickory (C. cordiformis) are not palatable without processing.

Hickory nuts can be difficult to remove from the shell as they tend to wrap around the nut meat. A set of wire snips and a nut-pick are two tools that are friends of the hickory forager.

One method of circumventing the need to separate all of the nut meat individually is to pound everything down into finer pieces and make “hickory milk” by boiling it in water. I am still experimenting with this method and will report back with what I have learned!

It’s important to make sure you’re only working with good nuts. Spoiled or rancid hickory nuts produce bright yellow or blue colors and usually smell off. These should not be consumed. Hickory weevils are also a possibility when foraging for nuts and desiccated nut meat that won’t be good for eating.

The characteristics of different hickories vary from species to species, but I’ll include identification characteristics that are consistent across all of them.

Two of my favorite species are Shagbark Hickory (C. ovata) and Pignut Hickory (C. glabra).

Identification:

- Pinnately compound leaves, alternately arranged, turning yellow in autumn

- Bark typically with intersecting ridges

- Usually with prominent end buds

- Twigs usually wirey

Foraging Roots and Tubers in Alabama

Another category that contains calorically significant wild foods. Much of our soil in Alabama isn’t ideal for producing large fleshy taproots in plants like dandelions or wild carrots. However, plants growing in water get around this problem!

Many of the important tubers in the state are aquatic. Examples include American lotus, wapato, and cattail! I have included American lotus in this article, but I want to work more with cattail and wapato before adding them here, so look out for them!

If you don’t want to miss updates like this, consider joining our mailing list!

American Lotus - Nelumbo lutea

American lotus is one of the most important wild foods in my area. They grow abundantly in shallow waters and produce tons of calories in the form of edible seeds and tubers.

You may need a canoe or kayak to get the seeds, but you’ll never have more fun gathering a wild food. The green seeds can be eaten straight away, and the brown/purple seeds with a tough outer coating can be stored long-term and then cracked to use. The seeds are typically available in the middle of Summer.

The other food product is their tubers. Lotus root from the Asian “white lotus” is a popular vegetable in East Asia. Despite being consumed for generations in North America, it has fallen out of common cuisine here. It’s time we bring it back! They are ready to be harvested in late Summer to Autumn.

Lotus tubers are delicious. They have a taste that is reminiscent of potatoes to me. My favorite way to prepare them is to boil them first and then make crispy lotus fries. I cannot get enough!

Identification:

- Aquatic plant with large, circular, floating or emergent leaves, often reaching 18-24 inches in diameter

- Leaves lacking a notch, having a distinctive central depression and are bright green, rising above the water surface on stout stalks

- Large, showy, pale yellow flowers, up to 10 inches across, with numerous petals and a central, cone-like structure

- Flowers bloom in mid to late summer

- Fruits are a distinctive, conical, seed-head structure with numerous seeds in pits

- Grows in shallow, muddy waters of ponds, lakes, and slow-moving rivers

- Can form extensive colonies

Spring Beauty - Claytonia virginica

I call them “fairy potatoes”. Spring beauty is a lesser-known wild food. In my area, they flower by the thousands every Spring (hence the name)! What people don’t know is that they are holding a buried treasure underneath.

Spring beauty tubers are, unfortunately, very small. I’d be excited about finding one about the size of a quarter to half-dollar. Nonetheless, they have a great taste, similar to a potato, and can be readily found in the Spring. I think more people should be growing this native wildflower!

Identification:

- Small, low-growing, perennial herb

- Leaves are slender, grass-like

- Delicate, small, white to pink flowers with five petals, each petal with darker pink veins

- Flowers bloom in early spring, often forming a carpet-like appearance in wooded areas

- Produces small, round, brownish capsules as fruit

- Prefers moist, deciduous woodlands and forested areas, often found in rich, loamy soils

- Tubers are small and edible, resembling miniature potatoes

Foraging Wild Mushrooms in Alabama

Wild mushrooms hold a special place for many people. For some, it’s rooted in fear of getting poisoned. For others, it’s for the potential of some of the most delicious wild foods that can only be gathered from the wild!

Fungi get a bad rap for being “dangerous,” which is a misattribution. Wild mushrooms are no more dangerous than wild plants. In fact, I would say that mushrooms are safer because while some plants are dangerous to touch, causing severe skin reactions, the same is not true for mushrooms!

Consuming any species without knowing what it is is dangerous, regardless of the kingdom it comes from. This is why you must be 100% confident in the identify of what you are consuming. This is covered more in our How to Start Foraging article, so remember to check it out if you haven’t yet!

I’ve included abundant and easy-to-recognize mushrooms in this article, like Chanterelle and Lions Mane. If you want a more comprehensive list of wild mushrooms in Alabama and the Southeast, see our Mushroom Foraging Seasons of the Southeast article.

Also, if you’d like to join a group of people to learn about mushrooms, I highly recommend checking out the Alabama Mushroom Society!

Chanterelles - Cantharellus

Chanterelles are the most abundant wild gourmet mushroom in Alabama. I far prefer foraging them over morels. They are everything morels are not: easy to find with a long season. I encourage you to go foraging for morels in Alabama. Their peak season typically falls between June and July when we have been getting consistent rainfall.

Chanterelles are delicious and work well in a variety of dishes. In my opinion, this is one of the best mushrooms for beginners.

There are a few lookalikes to chanterelles, the more dangerous of which is the jack-o-lantern, but with a few details, they are easy to tell apart. The two simplest ones are that jack-o-lantern (Omphalotus illudens) have “true” blade-like gills and typically grow as large clusters out of wood. Chanterelles have “false” ride-like gills and typically grow singly out of the ground. Look out for our full article on distinguishing chanterelles from other mushrooms. (You can join the mailing list to be notified when it is released)

If you want to find Chanterelles in Alabama, I highly recommend you learn how to identify oak trees. During chanterelle season, I pretty much ignore every other tree. If you’d like to learn more about identifying trees like oak, you can check out our free Tree ID Basics class!

The identification section will be for the Cantharellus lateritius group, one of the more common chanterelle species in the South.

Identification:

- Distinctive, funnel-shaped caps, typically 2-5 inches wide, with edges that are often wavy or lobed

- Cap color ranges from bright yellow to orange-yellow

- Underside of the cap smooth or with forked, shallow gills or vein-like ridges, running partially down the stem; these are typically the same color as the cap

- Stems are thick, smooth, and the same color as the cap, tapering downward

- Inner flesh is white and firm, with a mild, fruity smell, and pulling apart like “string cheese”

- Typically found in deciduous and mixed woods, often near oaks, in late summer and fall

Chicken of the Woods - Laetiporus

Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus) was the first wild edible mushroom I ever foraged for! It is great for beginners as it has few lookalikes and is relatively easy to find in the woods. The two main species you’ll encounter are L. cincinnatus and L. sulphureus.

I used to gather a lot more of this mushroom, but these days, I’m really only harvesting it if I find in prime condition. I’m looking for springy, juicy inner flesh with bright colors. At this stage, I can press the mushroom while cooking and develop an amazing crispy texture on the exterior. Anything past prime and the pores become rigid, and I haven’t found a suitable cooking method to remedy that.

I’ve heard of people dehydrating the mushroom and using it for stock. This is something I haven’t experimented myself with just yet.

The three lookalikes that I think you could encounter are: Hapalopilus croceus, Trametes cinnabarina, or Piptoporellus. Look out for a detailed article on how to distinguish these. They do not have white inner flesh like chicken of the woods and are typically “woodier” than a prime chicken.

Identification is for L. cincinnatus, “White-pored” chicken of the woods—a species with superior taste to me.

Identification:

- Produces large, funnel-to-shelf-shaped fruiting bodies, typically growing from a buried root

- Bright orange to salmon-colored caps, fading to a paler yellow or white with age, usually with a white color on the margin

- The underside of the cap has small, white to cream-colored pores

- Texture is soft and spongy when young

- Found primarily on or at the base of living or dead deciduous trees, especially oak

Lion's Mane - Hericium erinaceus

Lion’s mane is one of the more abundant wild mushrooms found in Alabama. It looks like a large white “pom-pom” growing out of dead or dying wood and is very distinctive!

Look for them in the colder months, October-March, during good rainfall. Maple and Hackberry/Sugarberry are the trees I find Lion’s Mane on most often! (Check out our Winter Tree ID class to be able to find these trees without their leaves)

I like to cook these by slicing them, dry sautéing, and then crisping them up at the end in oil. It’s one of my favorite wild mushrooms to eat!

Identification:

- Forms a single, large, white, globular mass of long, dangling spines, resembling a pom-pom or a lion’s mane

- Spines are typically 1-2 inches long, giving the mushroom a distinctive shaggy appearance

- Found growing on dead or dying hardwood trees, particularly oak, maple, and beech

- Begins white and may yellow with age

- Flesh is white and firm with a mild, slightly sweet flavor

Morels - Morchella

Morels are arguably the most iconic edible mushroom you can forage for. Their appearance is peculiar and striking and they are delicious. Unfortunately, morels are not one of the more abundant wild mushrooms that can be foraged in Alabama. Our Spring season here doesn’t consistently produce conditions that are optimal for morels. Don’t be discouraged though, they certainly can be found here.

You’ll find your typical advice like looking for sandy/loamy forest soils and looking for Ash, Elms, and Tulip Poplar, but there is one additional association to add to your list that is more exclusive to the Southeast, privet.

That’s right, privet, the invasive bane of Southern forests and fields, is known to associate with morels. This was first described in Association between living roots and ascocarps of Morchella rotunda by Buscot and Roux where they found morel “mycelial muffs” forming around the roots of common privet, Ligustrum vulgare!

Before I discovered the paper, this association was told to me by Tim Pfitzer of Magic City Mushrooms based on his personal observations foraging for morels in Alabama!

If you are interested in foraging for morels in Alabama, you should check out the Alabama Mushrooms Society’s annual Morel Foray. It’s a great event and we find a bunch of morels every year!

Identification:

- Distinctive sponge-like, honeycomb cap, with pits and ridges, usually elongated and conical in shape

- Cap color varies starting gray, turning yellow, and finally brown at maturity

- Entire fruiting body is hollow

- The cap is attached directly to the stem, without any separation

- Typically grows 2-6 inches tall, but can sometimes be larger

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some answers to a set of questions that people often ask about foraging in Alabama.

- Q: What grows wild in Alabama?

A: There is a wide array of species that grow wild in Alabama. Notable edible species include: American Persimmon, Paw Paw, Wild Plum, Sumac, and Pokeweed. - Q: What weeds are edible in Alabama?

A: The following plants are often considered weeds, but are edible: chickweed, purple deadnettle, thistle, wood sorrel, dandelion, canadian wild lettuce, and more. - Q: What to forage in Alabama?

A: Though Alabama isn’t necessarily known for its foraging, it should be! Many edible species grow wild in the state, like American Persimmon, Black Locust flowers, Mulberry, Maypop, Blackberries, Blueberries, and much more! - Q: What berries grow in Alabama?

A: There are berries that grow in Alabama like blackberry, dewberry, black raspberry, blueberry, elderberry, and mulberry!

Conclusion

I really hope you found the article helpful! You can let me know if there are any other species you’d like me to cover by using the “Contact Us” button at the top or message me on Feral Foraging via social media.

Don’t forget to join our Foraging Discord community and check out my YouTube channel to learn every more about foraging in Alabama.

If you feel like you don’t have a place to go foraging, you can check out my Rules and Regulations of Foraging article to learn where it is allowed!