This step-by-step guide will teach you everything that you need to know to harvest and process lactuca species to make a wild lettuce extract!

Who is this article for?

If you are interested in using wild lettuce as an herb, if you have worked with wild lettuce before, but want to expand your knowledge of preparing it, if you have heard of the medicinal properties of this plant, or want to learn more about wild lettuce in general, this article on making wild lettuce extract is for you!

The contents of this article include:

- The history of wild lettuce

- A step-by-step guide to extract wild lettuce and learn how to make a concentrated wild lettuce extract

- The chemicals in wild lettuce and its herbal actions

- Where wild lettuce can be found -> see my article here

- How to identify wild lettuce -> see my article here

Do I sell wild lettuce extract?

The answer is no, however, I’ve teamed up with Christian from wildlettuce.com to bring you extremely high-quality wild lettuce products grown and processed here in the United States.

You can use code, ‘feral’ to get 10% off of your order!

History of Use of Wild Lettuce

“Wild lettuces” are a group of plants in the genus Lactuca that occur in the wild. The word Lactuca comes from the Latin root, “lactis,” meaning of or relating to milk. It gets this name because the plant, when cut, exudes a white “milky” substance.

The grocery store lettuce that we know and love is part of this genus and was cultivated from prickly wild lettuce (Lactuca serriola) one of the most widespread wild species.

Because of its traditional use as a treatment for pain and sleeplessness, common names for wild lettuce include, “Opium lettuce” or “Poor man’s opium”, however, it is important to note that wild lettuce is not an opiate.

No chemicals in the plant act on our opioid receptors, one of the reasons why many people actually prefer it. This is discussed further in the Chemicals of Wild Lettuce section. In this article, we will look at how to work with this plant to extract its chemicals into a form that we can use.

What is Lactucarium?

Some confusion may arise around the product called “Lactucarium.” In modern herbalism, it is often used to mean any concentrated extract of wild lettuce.

However, when reading through historic texts, lactucarium typically refers to the dried product of harvesting only the sap/juice of wild lettuce. [1]

Therefore, technically speaking, what we will be making today is not lactucarium, but a whole plant concentrated extract. Don’t worry though, we will not be losing any of the prized plant sap in our preparation!

Disclaimer

This article contains a combination of statements based on scientific studies and physical facts as well as my own experience and opinion. Sources for claims that come from outside of my own experience are provided.

This article is not to be taken as medical advice or opinion. Consult a medical professional before using an herb for medicinal purposes. You are responsible for the identification and use of any herb you put in your body.

Why I DON'T make Wild Lettuce Tincture

A common method of preparing wild lettuce is to make a simple maceration tincture by harvesting the fresh herb and simply blending it in alcohol. There is nothing wrong with the method per se, but in my opinion, it yields a final product that is not potent enough. The method described in this article will lead you through the steps of making not only a good extraction, but a concentrated and potent one.

If you are interested in making a strong wild lettuce tincture, I would highly recommend checking out this article on a method developed by the herbalist, 7Song.

Another herbalist, Sajah Popham, describes his method of making a strong tincture using a soxhlet extractor. I would love to try this one day, but at present, the tools required are not available to me.

In this article, most of the tools we’ll use can be commonly found in a typical household in North America.

Where to Find Wild Lettuce

For an in-depth guide on the locations where wild lettuce can be found and information on growing the plant, see our Where to Find Wild Lettuce article!

Most wild lettuce plants are pioneer species. They grow and thrive in disturbed areas. They do not seem to mind even the hard clay of the Southeast. I find most of my wild lettuce in open fields that have not been mowed yet.

Wild lettuce species are weedy annual or biennials, heavy seeders, and grow primarily in disturbed areas. There is little to no concern with over harvesting, just make sure to leave a few individuals behind to disperse their seeds for the following season!

Which Species of Wild Lettuce can be Used?

There are over 50 species in the wild lettuce genus. While Lactuca virosa, the European variety, is the most well known, it is far from the only species with the herbal action that we are after.

In my personal study of the plant, I have made preparations from both prickly wild lettuce (Lactuca serriola), and canadian wild lettuce (Lactuca canadensis) and they both worked just fine for me. It would not surprise me that more members of this genus could be used for the herbal action described than not. So to me, I don’t think it’s important to worry so much about if you have the “right” wild lettuce. However, it is important to make sure that the plant you harvest is indeed wild lettuce, and for that you can read over our comprehensive How to Identify Wild Lettuce article.

In my area of the Southeast, prickly lettuce (Lactuca serriola) grows abundantly and it is my wild lettuce of choice because it is easy to dry before processing. We will discuss why drying is important in a following section.

Overview: How to Make Wild Lettuce Concentrated Extract

- Positively identify wild lettuce

- Harvest wild lettuce plants

- Isolate the plant leaves

- Optional: dry plant material

- Extract the plant in alcohol

- Extract the plant in water

- Evaporate liquid to concentrate the extract

- Store and use in preferred form

Further, all of the tools that I use for this process can be found on this page. (Minus alcohol used and pots/bowls)

How to Harvest Wild Lettuce

As we mentioned before, if you cut or break part of the plant, you’ll notice that it will exude a white resinous substance. In plant terms, this is called latex, and it contains some of the important chemicals which have been discovered in the plant such as Lactucin and Lactucopicrin [2] (Read more in the Wild Lettuce Chemicals section). Because of this, some sites you read will recommend harvesting the sap in isolation by slowly scraping it from the plant or leaving it to drip into a container. Please, save yourself some time and frustration… do not bother with this. Simply harvest the entire plant!

Latex Allergy

A quick aside, the “latex” in wild lettuce is not the same as the “latex” that is commonly associated with latex allergies. Latex allergy typically stems from an allergy to the proteins of the Hevea (rubber tree) plant (which are not present in wild lettuce) or chemicals used in the processing of Hevea latex. (From OSHA – “Some synthetic rubber materials may be referred to as “latex” but do not contain the natural rubber proteins responsible for latex allergy symptoms.” [3]) The main allergy of concern when it comes to wild lettuce is that some people experience contact dermatitis from the plant sap. Be cautious if this is your first time working with the plant.

By harvesting the whole plant you’ll get far more plant material including the prized latex which is of course, in the plant. It will be far easier and more efficient for you.

Get my foraging guide!

Learn an amazing wild food for each month of the year with my guide, Foraging through the Seasons!

Enter your email below to have this FREE guide sent straight to your inbox!

When to Harvest Wild Lettuce

Should you harvest before the plant flowers? Or after? Personally I will harvest any time around flowering when the plant has bolted so it is easy to gather a lot of it quickly. One study did find that the bolting stage is the optimal time for some of the constituents in wild lettuce that may be responsible for the medicinal effect. [4] However, I don’t think it is worth overly optimizing this step which may yield marginal benefit. The way you prepare your extract is far more important and that is what we’ll learn next.

Initial Plant Preparation

Once you have gathered your plants, you can dry them for longer term storage or use right away fresh. I have done both and they both work fine, but I do have a preferred method.

Either way, I first strip the leaves off. I have tried to use the stems in my extract, but in my experience the stems have not been worth the trouble of drying to break down. If you have a very strong (stronger than a Vitamix) blender it may be easier and worth the trouble.

Stripping the leaves can be done very quickly. I hold the plant and run my hands down the stem opposite the direction of growth and they fall off easily. Some older plants develop sub-stems that originate from the original stem and can make leaf removal a little more tedious which is another reason I tend to harvest slightly younger plants.

Starting with Fresh Plant Material

If you want to process straight way with fresh material, add the leaves in a blender with enough of a high-proof alcohol (190 proof is what I use) so that it will blend smoothly. I blend the leaves down as small as I can to increase surface area and speed up extraction.

We have essentially made a maceration wild lettuce tincture at this stage. I leave it to extract for at least several hours, but usually 1-2 weeks in a jar at room temperature. However, my preferred starting method is actually with leaves that I have dried, and I will tell you why.

The Importance of Alcohol for a Strong Wild Lettuce Extract

The initial extraction in alcohol is crucial. I have done experiments extracting the same wild lettuce: one with only water and another with an initial alcohol extraction followed by water. Lactucin (and Lactucopicrin), mentioned before, are bitter chemicals [2], so we can use that as an indication of strength. Every time that I have done an extraction using only water, the taste was quite mild. However, when alcohol is used first, my final wild lettuce extract will be intensely bitter. We can predict more bitter means stronger as well.

I want the alcohol ratio at the first step to be as high as possible. With dry plant material this is easy to do with a small amount of high-proof alcohol because the plant does not contribute any water. However, fresh plant material does contribute water, so unless I use very large amounts of alcohol (which is expensive and not something I want to do) the ratio will be lower. This is why I start with dry plant material.

How to Dehydrate Wild Lettuce

To dry, my preferred method is using a dehydrator. I’ve tried sun dehydration in the past, but I usually find that it yields a product that has degraded somewhat. A dehydrator is consistent, thorough, and leaves the plant material as green as when I picked it!

I highly recommend the dehydrator that I use, not just for wild lettuce, but other foraging projects as well. A dehydrator can be an essential tool to a forager to easily preserve their harvest.

Link to the Dehydrator that I use (and all other tools for this process as well)

Starting with Dry Plant Material

With the wild lettuce leaves dried, I first use a blender to break them down into smaller pieces.

Place the wild lettuce in a bowl and weigh how much you have. I take that weight, and add between 4-5 times that amount in alcohol at minimum. Then I leave it to extract for at least several hours and up to several days.

At times I have used some gentle heat (below 180 degrees with the lid covered) during the alcohol extraction stage. I have not fully tested how much this affects the final strength of the extract, but I have noticed that after applying gentle heat and leaving out overnight, a “gummy” layer forms on the surface, perhaps an indication of a better extraction.

Heated Water Extraction

This is where our two different initial starting points join. After the extraction in alcohol, I add water until it is roughly double the volume (or more) and then put on low heat so that the liquid rides around 180 degrees Fahrenheit, stirring occasionally for a couple hours, and keeping the lid covered in between.

Once that is done, we need to strain out the plant material from the liquid. I use a cloth filter to squeeze out as much of the liquid as possible. Sometimes I use a potato ricer to squeeze the last bit of material. I’ve found this to be very helpful if I started with fresh plant material, but not yielding much more than just the cloth filter with dry.

Concentrating Wild Lettuce Extract

With the extraction complete, we now have a base liquid extract. There is just one problem, it is far too diluted to be of much use. We will remedy that by slowly evaporating off the liquid in the extract, thus concentrating it down. This makes our preparation much stronger and easier to preserve.

Again keeping the temperature below 180 degrees, but this time with the lid off, I allow the liquid to evaporate until it’s down to about 1/8 of the initial volume. If you started with a large pot, it may be helpful to transfer to a smaller pot to avoid burning. I’ve even placed the solution into a metal mixing bowl and into an oven as low as the temperature will go (~170 degrees F). The trick is low and slow. This is even more crucial as the extract becomes more concentrated and the risk of starting to burn everything increases!

You should being to see it become more viscous. If it gets to the point of having a thick consistency like that of molasses, you can pour everything into a jar and store in the fridge or freezer long term. However, I prefer to go to one step further before the liquid has become quite that thick.

I pour everything onto silicone pads that can be placed into my dehydrator. The I dehydrate very slowly, usually around 135 degrees F. This eliminates the risk of burning while allowing the water be to thoroughly remove extract. When it is done, you’ll be left with what amounts to a black, resinous, tar-like substance. If the moisture has been removed completely, it should be quite easy to peel away, but if some parts are still sticky all you need to do it place back in the dehydrator for a longer period of time and eventually it will remove very easily.

Final preparation

This is the most concentrated form of our extract. For the extract that was made for this article, I used 200g of dried leaves and ended up with a final extract weighing 58g. Some people will take a slightly different approach, spreading the liquid extract very thin during dehydration and then blending into a powder after. I’ve tried this, but it is not worth the trouble for me. For one, my dehydrator doesn’t seem to work well with spreading the material that thin. For another, I find that when I get a great extraction from using alcohol at the beginning, it is too resinous to blend into a powder easily. Last, I don’t like to take my herbs as pills, but that is just a personal preference.

The one problem that I have with the current form of our extract is that it is very tedious to take. So let’s fix that.

Adding Alcohol to Liquify and Preserve

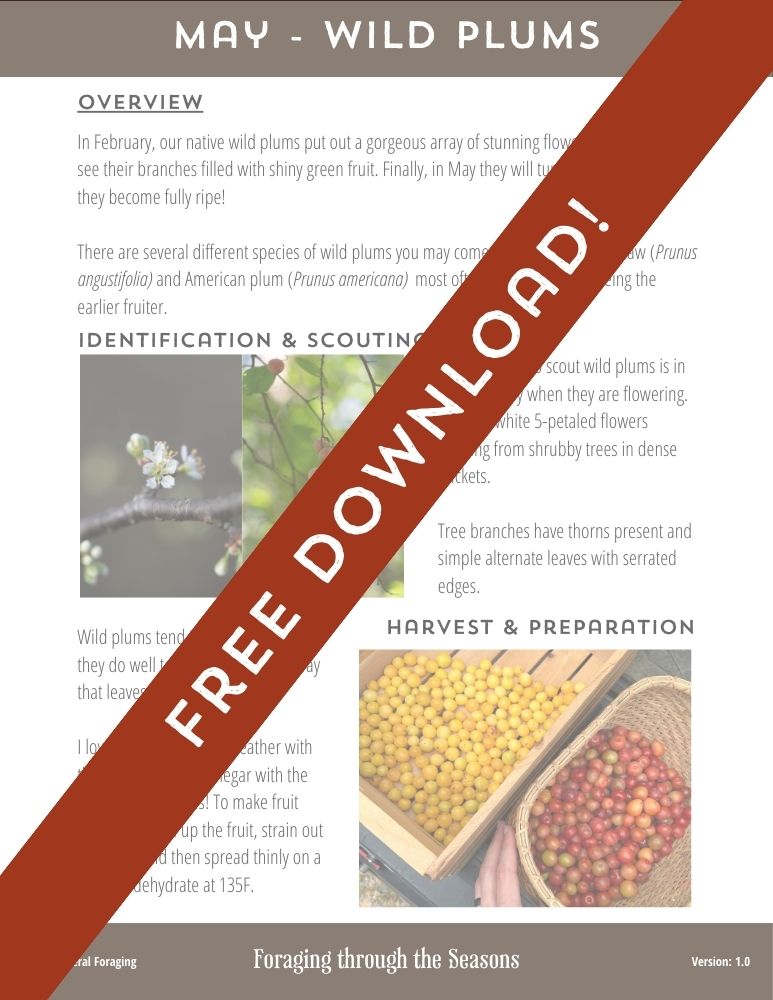

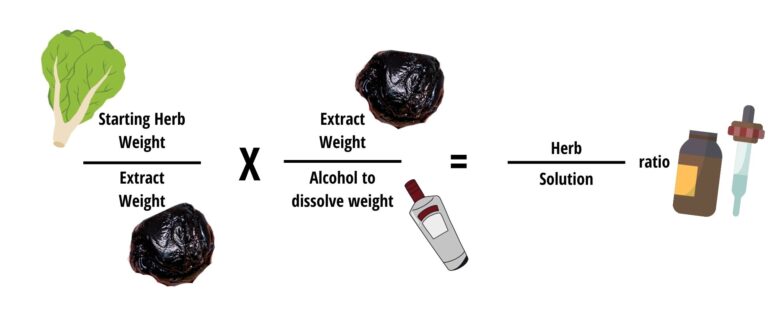

I initially got this idea from Sam Coffman of The Human Path and Herbal Medics. I add 40% alcohol vodka, at 4x the weight of the extract, so it will dissolve. As a liquid, it is now convenient to take with a dropper while remaining shelf-stable. This is the final form of my concentrated wild lettuce extract.

If you have been following along with the process, you are done. Congrats!

Dosage

For dosing, I use about 2-3 dropperfuls with some water in the evening for sleep. For the extract that I made, that comes out to be about 1.4-2.1g of dried herb. Every extract will be a little bit different in strength depending on your process, so start with a small amount and slowly increase until it produces the effect you are after. You can see how I calculated how much equivalent dried herb that I am taking per dose in the Appendix.

Is Wild Lettuce an Opiate?

Because of the herbal action that Wild Lettuce is most notorious for, it is not a surprise that it has nicknames such as “Opium lettuce” or “Poor man’s Opium”. This has lead to the idea that wild lettuce doesn’t just work like opium, but actually contains opium. Let me set the record straight: wild lettuce does not contain opioids.

The effect of opioids comes from their action on opioid receptors in our bodies. wild lettuce does not contain any chemicals that act on our opioid receptors and thus wild lettuce not an opioid.

However, I will note that, at least to me, this is a desirable thing. After all, the harsh side effects and habit forming of nature of opioids are far too well known in modern society. In my personal experience with wild lettuce, I have never experienced adverse side effects, nor felt like I was developing a habit or dependence.

That being said, this does not mean that one shouldn’t consult with a medical professional before using wild lettuce or replacing other options with wild lettuce.

Wild Lettuce Chemical Composition

Now that we know what wild lettuce isn’t, we can take a closer look at what wild lettuce is.

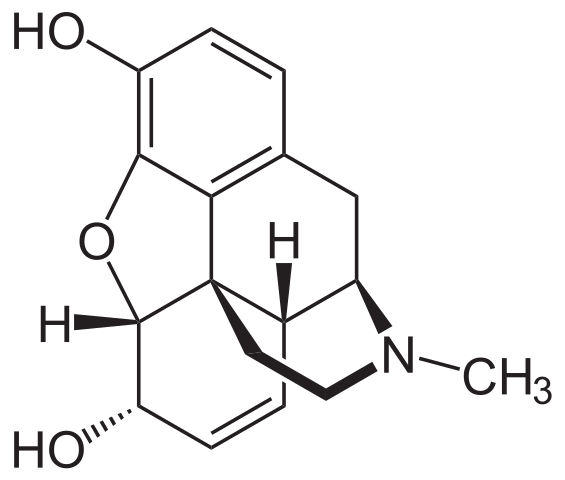

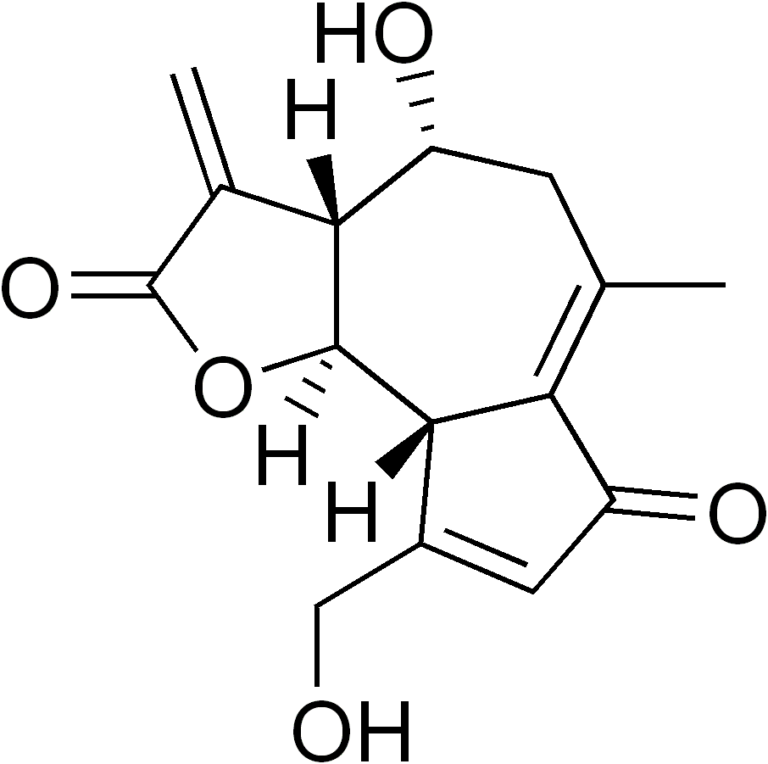

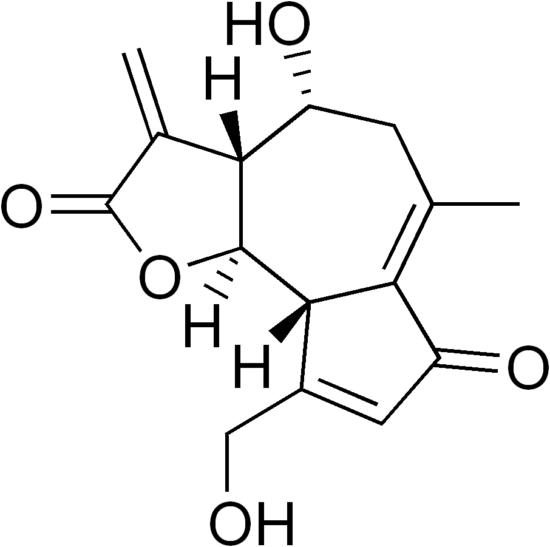

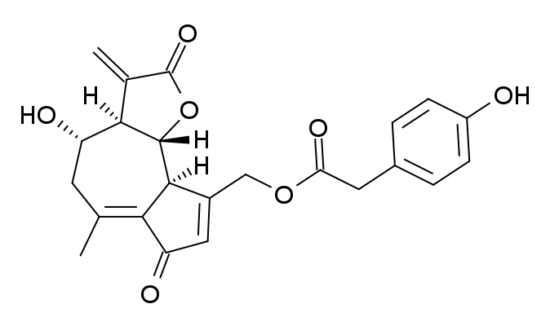

So far, the two primary constituents identified in wild lettuce thought to be strong contributors to its effect are: Lactucin and Lactucopicrin [2]. Both of these chemicals are in the chemical group sesquiterpene lactones a subdivision of terpenes. If the term “terpene” sounds familiar to you, it is because terpenes are widely used throughout our world. Terpentine from conifer trees is a terpene and rubber is as well. Terpenes are not alkaloids. Sometimes people use the term “alkaloid” to refer to any plant chemical, but this distinction is important particularly because it can lead to further confusion between opium (which is an alkaloid) and wild lettuce.

Lactucin

Lactucin is a bitter chemical that has been demonstrated to have analgesic (pain relieving) and sedative actions in mice [2]. Further investigation into the action of Lactucin finds it to be an “adenosine receptor agonist” [6 – note, this source only references that Lactucin is an adenosine receptor agonist, currently, I have not found strong evidence to suggest that it is]. In other words it increases the action of adenosine in our bodies. You may recognize adenosine because the well-known chemical caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist [5], **which leads to us being more alert. Lactucin does the opposite! So it makes sense that this herb makes us feel more tired or relaxed.

Lactucopicrin

Lactucopicrin was found in the extract used in the previously mentioned study on mice. Further analysis of this chemical has found it to be an “acetylcholinesterase inhibitor” which are used for an array of medical applications. The chemical can also be found in dandelion and chicory root which makes a lot of sense because those two plants are in the same tribe of the Asteraceae family as wild lettuce.

Other Chemicals

Wild lettuce extract undoubtedly contains important chemicals in addition to two identified here, but with current research these have been the ones identified so far.

Toxicity and Safety

A toxicology report in the British Medical Journal from 2009 describes 8 patients (likely from Iran where the hospital was) who were admitted to the hospital with what was thought to be “acute wild lettuce toxicity”. [8] None of the patients experienced fatal nor permanent issues as a result. Exploring the report further, it seems to point to these patients having recently consumed a “great deal” of raw wild lettuce. (The study says L. virosa, but it’s more likely to have been L. serriola)

They has a range of symptoms from dilation of the pupils, to blurred vision, dry-mouth, and anxiety. These symptoms are consistent with hyoscyamine toxicity (which the article hypothesizes is where their symptoms originated). Hyoscyamine is an alkaloid found in famous toxic plants such as Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna. However, it is also medically significant and in proper dosages, commonly used in modern pharmaceutical medicine.

Does this mean that wild lettuce contains dangerous amounts of the tropane alkaloid hyoscyamine? I have my doubts. I investigated the occurrence of hyoscyamine in wild lettuce and tracked down an article from 1892 (a very long time ago scientifically speaking) which claims to have found hyoscyamine in the plant in trace amounts. [9] I also found another article from 1933 that attempted to replicate the results of the 1892 and failed. [10] At the very least, if hyoscyamine is present in wild lettuce, it does not appear to be consistent across different species, throughout the life of a single plant, or even within a species. Further study is needed.

I have never consumed copious amounts of raw wild lettuce and don’t intend to (it’s very bitter). However, I have taken large doses of my extract and know of other herbalists that have consistently taken large doses without experiencing any of the issues outlined in the 2009 toxicology report. (See interview with Sajah Popham of Evolutionary Herbalism [11]) Are we certain the patients in question did not misidentify wild lettuce for something else? Was it the only thing they consumed? Did the environment of the plant play a role? We’ll never know.

All this is to say, one should always be careful when working with a new plant species. As we stated before, you are the responsible party for any herb that you consume.

We have written about this more extensively in our Is Wild Lettuce Toxic article.

Appendix

References

- John Uri Lloyd, 1911: The History of the Vegetable Drugs of the U.S.P.

- Analgesic and sedative activities of lactucin and some lactucin-like guaianolides in mice

- OSHA – Latex Allergy Overview

- Metabolite Profiling of Sesquiterpene Lactones from Lactuca Species

- Caffeine enhances acetylcholine release in the hippocampus in vivo by a selective interaction with adenosine A1 receptors

- Prospects of wild medicinal and industrial plants of saline habitats in the Jordan Valley

- Application of the In Combo Screening Approach For the Discovery of Non-Alkaloid Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors from Cichorium intybus

- Wild lettuce (Lactuca virosa) toxicity

- The Existence of a Mydriatic Alkaloid in Lettuce – T. S. Dymond – 1892

- The Mydriatic Activity of Lactucaria by the Munch Method – 1933

- Wild Lettuce Benefits with Sajah Popham | Wild Lettuce Pain Relief (Video Interview)

Calculation of Extract Strenght

I like to use dry herb equivalence as a first guess of dose strength in my wild lettuce preparations. To do this, take your starting material weight and divide it by the weight of the final solution you product. (Extract weight cancels out) This will give you weight of dried herb per weight of solution. Note: this cannot account for one extract being better/stronger than another. So it is always advices to start low and slowly increase dose, not the other way around.

Final Thoughts

Wild lettuce is an plant that has been used for a long time! If you are interested in implementing the extraction method outlined in this article, see our companion articles on Where to Find Wild Lettuce and How to Identify Wild Lettuce.

Happy hunting!